Ancient India and the Good Life. How did ancient Hindus imagine happiness? How did Pāṇḍavas think about work-life balance? Let's use the wisest of ancient texts to ask the most pressing of modern questions: How to live best? A thread:

Ancient Indians learnt from nature. Animals have symmetrical faces; a perfectly rounded rock goes a long way. How can human life be made symmetrical, proportional and well-rounded? Ancient India's answer: By the practice of Puruṣārtha. A perfect life must tick off 4 boxes:

Artha (Wealth) Kāma (Pleasure) Dharma (Virtue) Mokṣa (Freedom) The 4 aims of life according to Sanātana Dharma. First mentioned in the Vedas, these 4 aims became a subject of debate among the Pāṇḍavas in Book 12 of the Mahābhārata.

Sanātana Dharma knows that man is a strange animal. He walks with one foot in the material world, another in the spiritual. Artha and Kāma matter, as physical beings who feel pleasure and pain. Dharma and Mokṣa matter because we are freedom-loving, truth-seeking spirits.

But how to prioritize? What if acquiring Artha and Kāma comes at the cost of Dharma? How can we be Dhārmika in this age and compete with the adhārmikas who are ready to leave morality behind? Is Mokṣa possible in 2022? Leaving aside Mokṣa, Vātsyāyana writes in Kāmasūtra:

“By dividing his time, man cultivates the three aims in such a way that they enhance rather than interfere with each other.” Wealth, pleasure, and virtue must interplay in mutually productive ways. King Purūravas once met Dharma, Artha, and Kāma as physical gods.

He paid homage to Dharma but ignored the other two. So they cursed him. Kāma cursed the king that he would be separated from, and pine for, his wife Urvaṣī. Artha cursed him that greediness would totally hijack him. Purūravas, overtaken by greed, stole from everyone.

Some people, impoverished and angered, killed him with “blades of sharp sacrificial grass.” Lesson is clear: when you ignore important aspects of life - Artha and Kāma - you develop a one-sided life that ultimately hurts you. Even though Vātsyāyana wrote his treatise on Kāma

He advised his readers to prioritize Dharma if they absolutely had to choose. “When these three aims - Dharma, Artha, and Kāma compete - each is more important than the one that follows.” Best to balance all three:

This is where Kauṭilya comes in with a counter-point. In Arthaśāstra he writes: “Artha (sound economics) is the most important; for, dharma and kāma are both dependent on it.” How can a man be virtuous if he’s fighting a losing battle with poverty and pain?

It is Artha - sound financials - that allow a king to maintain an effective standing army. Kauṭilya writes that unpaid soldiers “either go over to the enemy or kill the king.” To be run over by external foes is not conducive to the pursuit of either virtue or pleasure.

If Kāma, Artha, and Dharma are the “what and how” of life, Mokṣa is the “why.” A rich, virtuous person who enjoys all pleasures still has an unmet yearning - To be free. Every pleasure enjoyed and every power wielded still ties us down - In systems, expectations, needs.

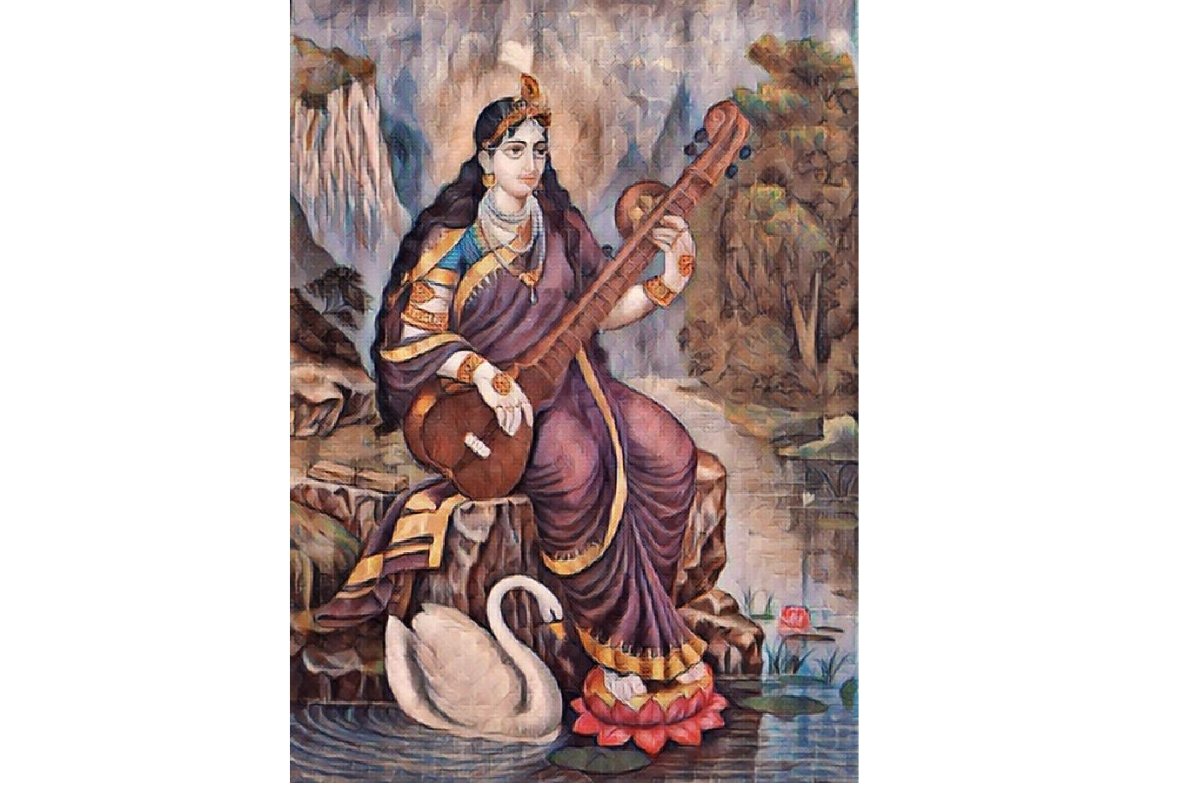

If a picture can speak a thousand words, a symbol can speak a million. When the Ancient Hindu mind visualized Mokṣa, it imagined Goddess Sarasvatī with a swan. Sarasvatī represents knowledge while the swan represents the discriminating talent for separating milk from water.

The discriminating talent to tell good from evil gives a swan the magical ability to move without making a ripple. Making it the perfect symbol for Mokṣa: Mokṣa is not an exit from the world but such a deep understanding of it that all resistance disappears. You simply glide

In the Śāṅti Parva, the longest book of Mahābhārata Ṛṣi Vidura discusses, with the Pāṇḍavas, the order of importance of the four aims, Vidura: “Adopt Virtue. Let not thy heart ever turn away from it.” Without Dharma, Artha and Kāma are on shaky legs.

While Ṛṣi Vidura saw virtue as a foundational layer, Arjuna disagrees: “With the acquisition of Wealth, both Virtue and the objects of Desire may be won.” Arjuna's channeling his inner pragmatist Material well-being clears our mind for the pursuit of virtue and wanton desire

Bhīma comes in with a unique perspective: “One without desire never wishes for wealth. One without desire never wishes for virtue. One who is destitute of desire can never feel any wish.” Desire is the motor of life. Without desire, we have no energy for anything else.

This debate from the Mahābhārata continues to this day - on our dinner tables, over the internet, and in our hearts. Wisdom is in the vision of integrality Here @oldbooksguy investigates the Puruṣārthas and ancient India's perspective on well-being

brhat.in/2022/08/11/how…

In the following piece, discover how ancient Indian ideas stack up against our modern notions of well-being! Contemporary psychology and Purusharthas - what are some similarities, and important differences?

memod.com/jashdholani/ho…